by Benjamin Ransom, UChicago News

Babies learn languages across cultures, under wildly different circumstances. Some children are spoken to in high-pitched, sing-song voices tailored just for them, while others grow up hearing adults that happen to be in their environment.

Yet somehow, it always works—and linguists want to know why.

It’s just one of the puzzles around language that researchers at the University of Chicago are working to solve. They’re also examining questions about how language shapes thought and what words capture our attention—such as in a compelling religious sermon or political speech. Students in the College are playing a key role in these investigations, using tools from attention-tracking software to AI-powered semantic analysis to make hidden connections.

The enigma of how babies learn language is what drew second-year linguistics major Tessa Bracken to the field.

“No one really knows exactly how infants acquire language," said Bracken. “I was fascinated by this process that’s such a mystery.”

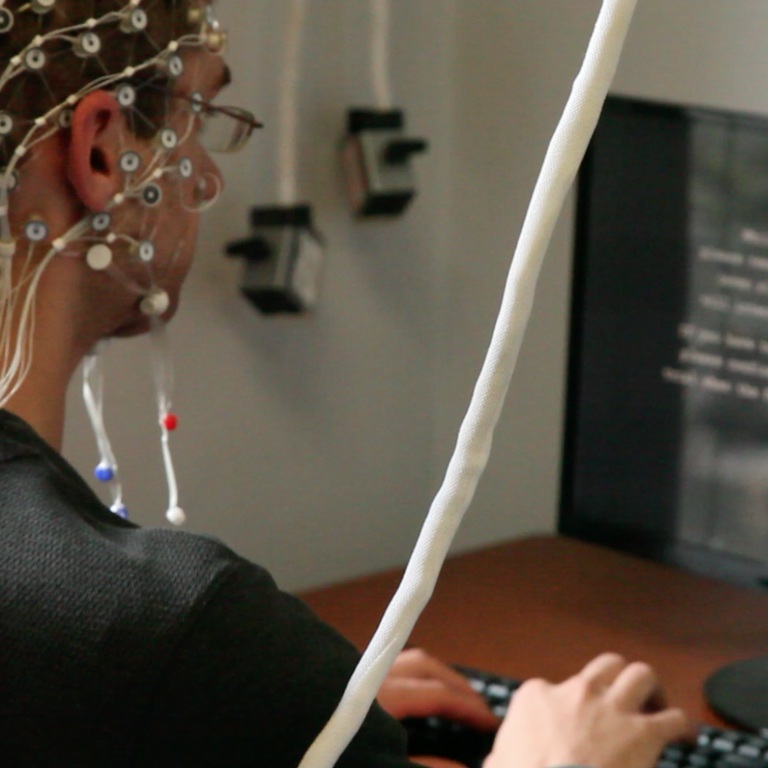

As a research assistant in the ChatterLab, directed by Prof. Marisa Casillas, Bracken spends hours annotating videos of babies listening to different types of speech. Using specialized software, she tracks where infants look, how long they stay focused and when their attention wanders.

Among other things, the lab is testing whether babies across different cultures—from Chicago to remote islands in Papua New Guinea—share the same preferences for how adults speak to them.

Learning language across cultures

Bracken and other researchers make annotations that track every flicker of an infant’s attention: when they look at a speaker, drift their attention away or when fussing disrupts focus.

This granular data helps the lab investigate infant-directed speech—the exaggerated, sing-song way many adults talk to babies—and test whether babies genuinely prefer it.

According to one theory, infants prefer this style because it is replicable, or easier for a child to reproduce. The idea is they are drawn to speech patterns matching their budding vocal abilities—the exaggerated prosody, slower tempo and clearer articulation model easy-to-imitate language.

But according to the data, this may not be the full story.

To test this theory, the lab compared how babies respond to infant-directed speech, adult-directed speech, and other-infant speech—recordings of other children talking.

"If replicability is what makes IDS preferable for infants, then infants would prefer other infant speech over infant-directed speech," Bracken explained. After all, children's voices should be even more replicable than adult baby talk.

But when the lab analyzed responses across cultures, the pattern didn't hold.

"The data was not consistent cross-culturally," said Bracken. "That was convincing evidence that replicability wasn't the full story."

For Bracken, these results are a reminder that while Americans commonly adapt and package their speech for their babies—it may be more of a cultural quirk than a key tool for acquiring language.

"In America, we believe we're attuned to how to raise a genius," said Bracken. "But all these factors we consider crucial probably don't impact language acquisition quite as much as we assume."

Bracken had a particular affinity for cultural and sociolinguistic insights from the research process. When comparing results from Chicago and indigenous cultures in Bolivia, Mexico and Papua New Guinea, she learned about a range of linguistic cultural contexts.

In some cultures, adults speak directly to babies constantly, using exaggerated intonation. But in others, such as that of the Yélî people of Papua’s Rossel Island, babies heard more ambient adult conversation but acquired language at similar rates.

A writer for the Chicago Maroon student newspaper and a student of classical languages, Bracken’s own journey to linguistics was sparked by the way different languages reframe ideas and interactions across cultures.

For example, her studies of Latin taught her about a grammatical structure that conveys background action or circumstance—in a way that flows beautifully in that language but sounds awkward in English, translating to phrases like "with the food having been cooked."

"The same idea is expressed so eloquently in Latin but doesn’t translate well to English, and that difference has always been really interesting to me,” said Bracken. “There's almost always a gap between the thoughts that we have in our head and how we express them to the outside world."

Decoding compelling language

Fourth-year linguistics major Surya Chinnappa shares Bracken’s interest in language and ancient wisdom, but brings an experimental and technological approach.

Working in the APEX Lab, led by cognitive psychologist Howard C. Nusbaum, Chinnappa is trying to decode what words and themes make religious sermons compelling to listeners. He analyzes subjective responses to Catholic homilies, coding them for semantic patterns—the kinds of meaning and topics that resonate with different audiences.

"It's a really interesting intersection, taking subjects that have historically been studied very productively by humanistic disciplines and introducing them to scientific study," said Chinnappa.

Participants rate sermons on a numeric scale for compellingness and answer related questions. Then, Chinnappa codes their responses for specific semantic dimensions—categories of meaning that emerge from data. By matching these reactions to specific meanings of words and themes, he aims to predict which of these are most gripping for an audience.

Through a collaboration with Father Edward Foley and the Catholic Theological Union, this method could eventually extend to other contexts where compelling language is important, like political speeches or marketing copy. For Chinnappa, the project represents a fresh approach to lexical semantics—the scientific study of words and their meanings—by combining linguistic analysis with psychology, statistical methods and the practical wisdom of religious practitioners.

"We are synthesizing psychological expertise and my own linguistic experience with the domain expertise of people who have trained in the theological practice of crafting these homilies," he said.

Eventually Chinnappa’s goal is to build all this expertise, and his manual semantic coding system, into an AI agent that can predict how compelling a sermon is based on its thematic content.

But while most AI systems reason in a “black box,” and train themselves to pick up patterns that humans cannot detect, Chinnappa wants his to operate transparently using human-defined semantic dimensions. He hopes this shows that adopting powerful computational tools doesn't have to mean sacrificing our ability to understand how they work.

"We want every step of the way to be intelligible and interpretable to human researchers so that we can continue to be in conversation with collaborators working on different aspects of the project," said Chinnappa.

Pushing the field forward

For both Bracken and Chinnappa, language research isn't just about cataloging patterns—it's about questioning assumptions. Both are bringing fresh perspectives to age-old questions, whether that's how infants master language or what words and themes move us.

"You're not just contributing to your professor's project, you're contributing to a long line of research on the larger topic of language," said Bracken.

As Chinnappa prepares for further studies in language and cognition, he also finds it fruitful to reflect on his own relationship to the field.

"The past few years, with advancements in computational complexity and artificial intelligence, have definitely shaken up the world in terms of how we think about language," he said.

While these students implement more sophisticated technologies, they also insist that human understanding must remain at the center. Studying language, their work suggests, doesn't just mean finding patterns—it means understanding what those patterns reveal.