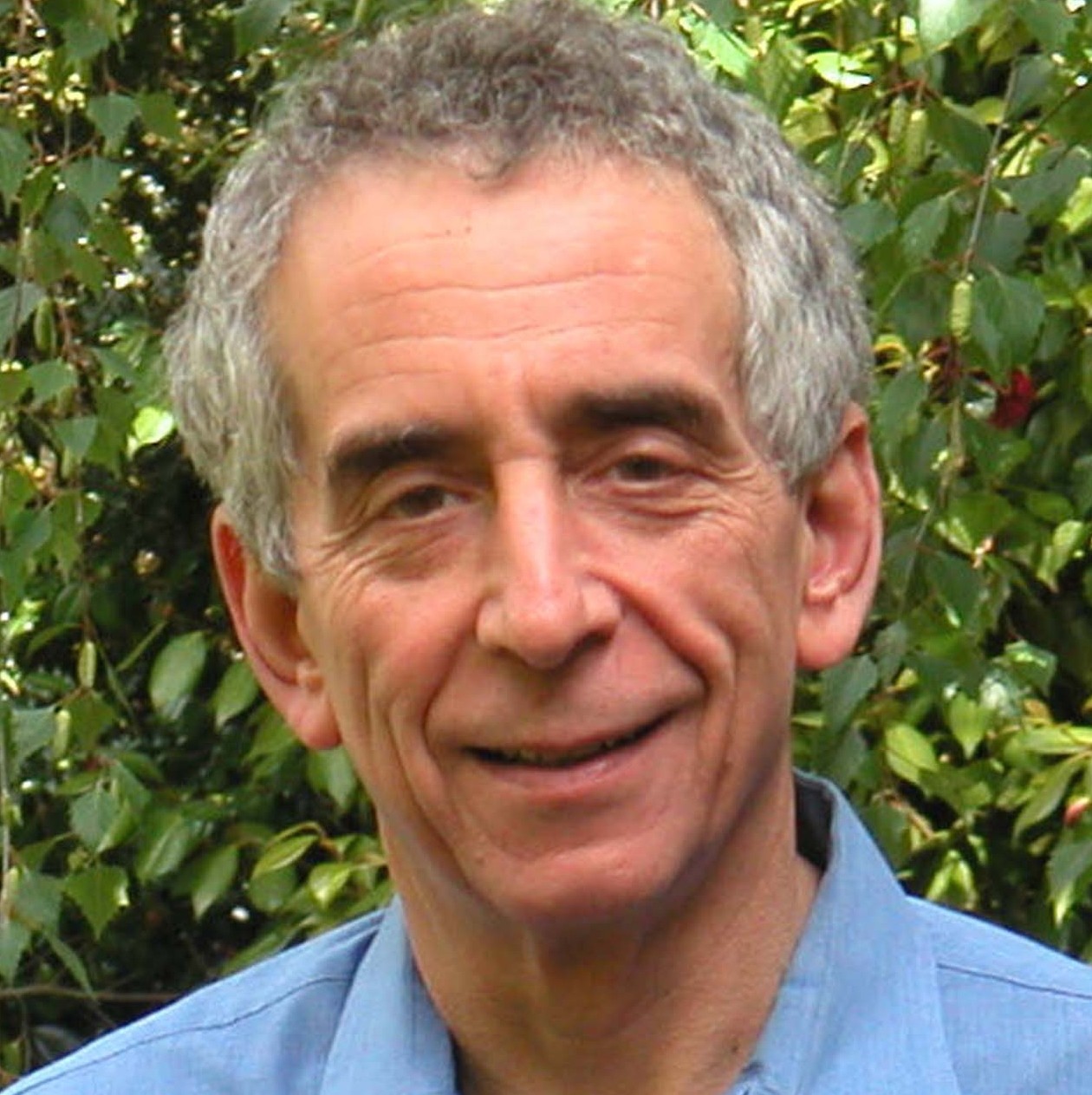

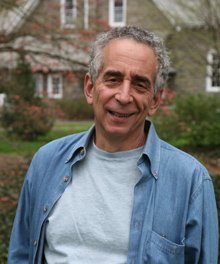

As a professor of psychology at Swarthmore College for 45 years, Barry Schwartz, PhD has focused his work on decision making, wisdom, and work satisfaction. His interests lie in the intersection between economics, morality and psychology. As one of the most notable public scholars on wisdom, his TED talks on wisdom and on choice collectively have been viewed more than ten million times. He appeared on the “Colbert Report” shortly after his book A Paradox of Choice: Why More is Less was released. His book Practical Wisdom: The Right Way to do the Right Thing, co-authored with Kenneth Sharpe addresses how to identify and cultivate wisdom and make ourselves healthier and wiser.

In this interview, Dr. Schwartz discusses how generalized incentives fail to enact change in human behavior, and describes his approach to teaching students about the importance of wisdom, and how practical wisdom may be cultivated in professional training programs through hands-on, real world experiences and mentorship.

Jean: What do you feel is wrong with our current systems and institutions, and how may they benefit from practical wisdom?

Dr. Schwartz: What we think in modern America and most modern states is that we can get what we want and need if we only come up with the right set of rules, bureaucratic structures and procedures and/or the right set of incentives. This incentive side is entirely embraced by economists and adopted from economics. If we make it worth your while to do the right thing, you'll do the right thing. If we force you to do the right thing with the threat of various kinds of sanctions, you'll do the right thing. We [Kenneth Sharpe and I] think that in any domain of life that involves interaction between human beings, there is no set of rules and there is no set of incentives you can design that will get you what you actually want and need, because people are different. Circumstances are different. You can’t craft rules and incentives to make allowances for the incredible diversity of situations that you face. A doctor may have a set of rules for how to diagnose cardiac disease, but the question is not just diagnosing the disease. It’s also how to get the patient to lose weight, exercise, quit smoking and stop drinking. There is no algorithm. There is no set of rules for that. The way you make patients ‘partners’ is by having enough empathy and insight into what life looks like to them and to know how to find a way in. If all you're going to do is diagnose, [then] you can't make patients ‘partners’, This is especially important in modern affluent societies where mostly we're trying to manage chronic diseases. You will never be a successful doctor, because you won’t get patients doing their part to manage chronic diseases.

For a teacher [a school district might say], “This is the best curriculum for teaching Math. Here it is.” Does that mean you just slavishly follow the curriculum? Well, if you want to be a mediocre teacher that's what you do. If you want to be a good teacher, you're asking yourself, "How do I tailor this curriculum so that Johnny will get the most out of it, and Janie will get the most out of it even though Johnny and Janie are really very different kids?” You need to improvise around a set of standard operating procedures. And what it takes to improvise is what Aristotle, and we shamelessly borrowed, called ‘Wisdom’. You need good judgment about what a particular person in a particular situation needs so that you can improvise around the rules. Incentives are an incredibly blunt instrument. As we know from education, all these efforts to make it worth teachers while for the kids to do well on standardized tests…all it has produced is kids who do better on a test, but absolutely no better in the classroom. How many times do we have to make the same mistake before people figure out this is not the way to get what you want?

Jean: That sounds right to me.

Dr. Schwartz: Well it is right [laughter]. What's saddening is that teachers know what's right; and what's happening is good teachers are leaving. A lot of people who stay in the profession are mediocre teachers.

Jean: I don't know if you have the answers to this but I’m going to ask. How do you begin to teach wisdom? How did we teach both the doctor to have the empathy they need along with the skill and how do we teach teachers to be able to teach the things that they need to teach but then also to be able to improvise?

Dr. Schwartz: It's a great question. How do you teach wisdom? This class that we taught for many years and students loved, we make it clear that the point of the class is not to teach them how to be wise. The point is to teach them why it’s important to be wise. The slogan that we have is ‘Wisdom is learned, but it can’t be taught’. What we mean by that is that the way you become wise is by having experience. The way you get it right is by getting it wrong and having somebody who's already been there watch you, guide you, and correct you. It's important to be in the space where you can make mistakes, where you can improvise, and get guidance by people who have already had the experience and know how to correct some of those mistakes. You need teachers who feel free to experiment with what they do, overseen by mentors who can help get them on the right track. The same goes for doctors.

There’s a wonderful piece an oncologist named Jerome Groopman wrote for the New Yorker some years ago called "Dying Words". It was about how doctors learn to tell patients that they are going to die. It's all about this particular 25 year old woman who was diagnosed with *** cancer and will probably be dead within three years. He describes the dance he does with her and her family trying to give her some hope while also trying to have her be realistic about what the future holds. The [dance involves] the subtlety with which he reads the cues on her face and the subtlety with which he appreciates the questions she's not asking as well as the question she is. It’s a masterpiece. Then he says, "I did a pretty good job here. How did I learn this?" He recounts how he learned it. “I learned it by being a bull in a China shop, because I never saw a doctor have this conversation. When you have this conversation with patients, you do it in your study and the door is closed. The residents have to learn on their own.” He said, “I started out thinking honesty is the most important. Just tell the truth. And I wrecked people's lives by doing that. Then I thought, well, I can't do that. So I started shielding them from the truth, and I wrecked patients' lives by doing that. Slowly over many years, because I made mistakes and at least was smart enough to learn from my mistakes, I kind of figured out how to do it."

That seems to me to be the way you become wise, but it requires an atmosphere in which improvisation is allowed and in which mistakes are allowed. In high stakes environments where people feel like you don’t have permission to fail, chances are you're going to end up with this system of rules and incentives that give up on excellence and just are insurance against catastrophe. Sometimes you do need to insure against catastrophe. You don’t want a heart surgeon who's learning with your chest open. So you got to make sure that the mistakes are not catastrophic mistakes, but in lots of areas in life mistakes are correctible. You have these kids for an entire school year. You make a mistake in October, you can fix it. It’s not heart surgery. I don’t think we live in an environment that's nearly permissive enough either about people taking initiative or about people failing. The only place that you see some of this, I guess, is in Silicon Valley where the slogan is Fail Fast. It's okay to fail as long as we don’t spend too much time and too much money going down that blind alley. It's better than “Don't Fail”, but “Fail Fast” isn't the best thing in the world. That's what I think. You learn how to be wise, but you can't be taught. You can't have a textbook, a primer, and ten easy steps to become wise. That’s just a self-deception.

Jean: How do you meet students where they are when teaching a course on wisdom?

Dr. Schwartz: Well, when we start out teaching the class, we are interested in having them see the importance of wisdom in the various professions that they're likely to be entering. Why did they need it in medicine? Why do you need it in law? Why do you need it in education? Why do you need it as a judge? Why do you need it as a parent? Why do you need it as a spouse? Well, they don’t know much about any of these things yet. So we decide to start with something they already think they are experts about. Why do you need it as a friend? So we begin by talking about friendship; and Aristotle devoted a fair amount of space to discussing friendship. Instrumental friendships- you give me something I need, I’ll give you something you need – is not very deep. But there are also character friendships, where the friends deeply respect and love one another and come to one another's aid just because it's the right thing to do. Our students spend two weeks thinking about and talking about friendship. They come to see the importance of what they do quite naturally because they have friends. They know. We have them think about this question: Your friend calls you up. She's getting dressed to go to a wedding and she wants you to come by and see how she looks. So you come by and she opens the door. She's in a fancy dress and she does a little pirouette and she says, "How do I look?" and actually you think she doesn’t look good at all. What do you do? This seems like a no-brainer to the kids. They say, "Well, friendship has to be based on honesty and trust. You tell her the truth." Then it goes into, "Really? Is that always the right thing to do? Does it depend maybe on whether she has an alternative? Does it depend maybe on if her self-confidence is so fragile that hearing, even though she obviously thinks she looks great, that you don’t think she looks great? Is this going to shatter her self-confidence? Maybe this is the right time not to tell the truth. Our students realize that the rule they have in their heads doesn’t do the job. Thankfully for them, it’s not a rule that they actually follow in everyday life, because they know all these things. I think it's an incredibly successful way to start because it really shows them that (A) they already know something about this and (B) it's really important to get this right. Now when we talk about careers where they don’t really have experience, they're very eager to see what the difference is between a wise doctor and an unwise doctor or a wise and unwise teacher. It gives them a set of lenses that they can use to interpret things that they don’t have as much familiarity with.

Jean: As described in your book, Practical Wisdom: The Right Way to Do the Right Thing, would you summarize a few examples of how practical wisdom can be cultivated through training methods in the medical and law professions?

Dr. Schwartz: Well, in the class and in the book we try very hard to make it as non-esoteric and un-academic as we possibly can. We talk about actual practicing doctors and what the obstacles seem to be to their practicing wisely. We describe examples of what we think is wise practice in action and what does it take to produce that. So there's a program at the Cambridge Hospital in Massachusetts. It’s affiliated with Harvard Medical School, where instead of doing the usual rotations in your third year of medical schools, six weeks here and six weeks there, you get assigned a panel of patients who you see for an entire year. You treat whatever it is that they come in the door with. The consequences of this are that you appreciate, that being a practicing physician, you’re treating people. You’re not treating organs. You need to know who the people are. You need to know what other problems they have that may not be medical problems. You need to know what kinds of recommendations you can make that they could actually carry out. You need to know how to follow up with them to make sure that they're doing the medically appropriate stuff. It’s a program for a small number of students with a lot of mentorship and oversight from experienced physicians. The students are just completely gaga over it. This is why they wanted to be doctors. I think this is an effort to develop wisdom in people who are going to need it every day as they practice medicine. Now, can this scaled up so that this becomes the model of medical practice generally? I don’t know the answer to that. It’s probably labor intensive and expensive, but some things are worth spending money on.

In law schools, the thing that the law students like the best are the clinics; where you are actually trying to solve real problems that real people have. I’m getting thrown out of my apartment. How can I stop the landlord from evicting me? I got roped into signing a terrible contract. How can I get out of the contract? The law schools don't much like teaching these because it's not prestigious. They often have adjuncts to teach the clinic, but this is what the students want. They want to be the lawyers. They want to know how to be lawyers and they realize that simply learning the law doesn’t tell you how to be a lawyer. It’s necessary. It’s not sufficient. If you’re doing family law, sometimes you want to be an advocate for the client. Sometimes what your client wants, you know she shouldn’t want. It’s not worth it. You’re so angry at your husband that you want to suck everything out of him to get even for the way he mistreated you, but what's going to happen to the kids if you do this? So I can help you get that, but that's not what you should be wanting. Sometimes my job as a lawyer is to counsel you about what you should want and sometimes it is to help you get what you think you want, and I've got to figure out what this situation in front of me is. Is it one of being a zealous advocate or is it one of trying to re-steer the ocean liner. This is what students love to do in law school. When you do this, this is how you learn to be a lawyer. You’ve got to know the law, but that's not enough. I think this is an incredibly practical approach. It's not esoteric. It's not academic. It really is: What are the problems we face in our day-to-day interactions with other people professionally or personally? What does it take for us to be able to solve these problems?

Barry Schwartz, Ph.D.

Dorwin Cartwright Professor of Social Theory, Swarthmore College