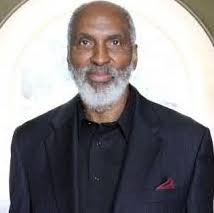

As an internationally recognized expert in the areas of civil rights and civil liberties, john a. powell is known for his work in a wide range of issues including race, ethnicity, poverty, and democracy. He is the Executive Director of the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, a Professor of Law, African American Studies, and Ethnic Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. He was recently the Executive Director of the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University. Under his direction, the Kirwan Institute has emerged as a national leader on research and scholarship related to race, structural racism, racialized space and opportunity.

The following is an excerpt from the documentary film The Science of Wisdom. The interview takes place at the International Symposium for Contemplative Studies in Boston hosted by the Mind and Life Institute.

In this interview, powell discusses wisdom in race relations, education, and law.

Jean: In past talks and interviews, you have discussed how race is not skin color, but rather a socially constructed concept. Please explain that a bit.

powell: The issue of race and the particularities in terms of race, in terms of whites and people of color, is actually complex, foundational, and constitutive. When you have a sense of normalcy in society, then you notice what's not normal. So, if we think about disabilities- which actually I don't like that term- we notice people with disabilities. We don't notice people who don't have disabilities. Those people are considered normal. So, there's one group of people who are normal that are not noticed and another group of people, who are not normal and who are noticed. In the Christian society, we don't notice Christians, but we notice Muslims. We notice Buddhists. We notice Hindus. In our society, the way race works is that the normativity is around whiteness. White people, in our society more or less, think of white people as just normal, just individuals, or just folks. Then we notice people who are different. We will say, “We want a diverse person”…meaning really we want a non-white person.

All of us have a race to the extent that we have race and it's all relational. There is no normal. I'm a vegetarian. I was in line one day getting ready to get something to eat and I asked the person serving if they had lasagna, and I said, “Is this lasagna vegetarian?” The person's response was, "This (meaning the meat lasagna) is the normal lasagna and this is the vegetarian.” And I said, “There's no normal lasagna. There's vegetarian lasagna and there's meat lasagna, but there's no normal lasagna.” So that's what I mean. The notion in our society is we notice increasingly when people of color show up, because in a sense they're not normal. The country was predicated on a certain set of white ideals and white beliefs, and I don't mean white in terms of skin color. Race is not skin color. Race is a set of sociological concepts that get lodged into our body, but it's been organized around a certain concept of whiteness that's now being challenged.

One of the things about being a person of color in the United States is invisibility. Earlier we talked about people of color being noticed, but being noticed is not the same as being seen. So, people of color are noticed and we're noticed often when we are at places we are not supposed to be, whether it's in a shopping center, whether it's in an upper middle-class white neighborhood or whether it's in a mindful meditation center. We get noticed but not seen. People need to be seen and to really see someone requires… [there is] a South African expression for seeing someone. They say to see someone you have to not only see them; you have to see their ancestors. You have to see their family, and you have to see their unborn lineage.

I gave a talk in a class where I would teach about the taking of Native American land and my students would say with some disgruntlement, “Why do we have to study Native Americans? This is not a class about Native Americans.” I would say we're not studying Native Americans, we're studying America. We're studying our own culture. Our culture is about the appropriation of our land. Our culture is about slavery. So, we study the Declaration of Independence. We study the Revolutionary War. We don't really want to study slavery. We've had a number of states in the country recently saying you can't teach slavery in this classroom because it makes people feel uncomfortable. Which people are they talking about? They are not talking about black people. They're saying you can't teach about the taking of land from Mexico because it makes people feel uncomfortable. Which people are they talking about? They are not talking about Latinos or Mexican-Americans. More importantly in some respects, they are not simply taking out the history of Latinos or the history of blacks or the history of Native Americans, they are taking away American history. People are aggressively trying to hold onto this narrow sense of what it means to be an American.

Jean: How do you define wisdom?

powell: There are different ways of thinking about information, knowledge, [and] wisdom. They're all different. We could even step back one step more. There's data, information, knowledge, and wisdom. The collection of data is certainly not wisdom. The collection of information is certainly not knowledge, and I would say the collection of knowledge is certainly not wisdom. Wisdom is understanding and embodying knowledge in a certain way so that it has a lived expression. That's one reason that in many societies we associate wisdom with age. There are certain things you just can't skip over. Reading about something in a book is not the same as living it, attaching not just a cognitive piece with it, but the heart piece with it, and the experiential piece with it. Experience is almost always ambivalent. Something happens. Was that good or bad? In the speed of the moment we oftentimes don't realize that experiences are ambivalent. We think they come with a tag line: that was a bad experience. Why was it a bad experience? A lot of contemplative practice is about slowing down, noticing, and being present. [It’s about] letting stuff in that normally is not welcome. It's like looking at, yet not seeing, the unconscious. It's like seeing and experiencing subtlety in ourselves and others. The more we can experience that, the more we can live with that, the more likely we are to inhabit wisdom. It also seems to be that knowledge has a harder edge. It's very definite. I know X, Y, and Z. Wisdom to me is much broader but it also has a softer edge- to be willing to be comfortable in the not knowing and not being sure.

Jean: How does wisdom play into being a professor of law?

powell: There's no way of bottling it up. You can't go to the store and buy it. So, a judge can be wise or not. A teacher can be wise or not. A parent can be wise or not. There are different schools and different expressions. So law aspires to be something which it can never be. And oftentimes law aspires to be something that's not even positive, like objective. That sounds good. It's not possible. It's not even necessarily desirable. When we talk about being color blind, it sounds like a good aspiration. The mind and science tell us it's not possible, certainly in our society. I would say it's not necessarily even desirable. Law pushes people in a certain direction. If you think about advocacy, it's a contest. It's intellectual gladiators: two sides fighting each other in a skillful battle, not for truth. What are they fighting each other for? [They are fighting] to win for their client. To win, that's the game with a bunch of rules within that. No, that is not wisdom. But there are parts of it that are actually quite wise. For example, there's something called the theory of big numbers which is the more information you collect the more accurate it would be. If you're doing an experiment and you look at 2 people, it doesn't tell you very much. You look at a thousand people the reliability becomes very high. When you take 12 people and put them on a jury and give them support, their ability to actually make decisions is actually quite remarkable. It's sort of playing on the wisdom that the whole is different than the sum of its parts. Now they have to get the right support and you can't have a jury necessarily of all people with the same biases. Which is why sometimes in race cases having an all-white jury is very problematic, but if you constitute a jury right and give it the right support, it actually leans in the way of wisdom. Well, whoever thought of that? The law thinking about that was pretty wise.

I don't think the law in a sense is a special avenue to wisdom. In fact, I think oftentimes it's the opposite. When my children were younger, they used to ask me, “Why do you need to do the work that you do and why aren’t you more depressed?” I'm not. I don't tend to be very depressed. And I said to do this work you need three things:

You need hubris. You need the willingness to take on things that some will say are completely crazy. To have hubris is to say you're going to try to make the world a better place. You know, when you're saying that when you're 15 that's one thing, but when you're saying it when you're 45, it feels quite different. It's like, well, you should have grown up. Stop chasing windmills. So you need hubris.

You also need humility. So even though you're willing to take on big things, you're willing to be wrong. You're willing to listen to other people. You're willing to learn. You need both of those things.

And you need love. You really need to care about people, about life, and about those you want to be in a relationship with.

If you have one or two of those, it's not good enough. You need all three. I feel like law oftentimes just has hubris. Oftentimes it doesn't have humility, and almost never has love. When you have all three of those things and you hold onto them for long enough, I think you're likely to stumble upon wisdom.

john a. powell, Ph.D.

Professor of Law, University of California, Berkeley School of Law

Reference

The Science of Wisdom, produced by the JJ Effect, directed by Jason Boulware