Robert Sternberg, PhD is a professor of human development at Cornell University. Before his professorship at Cornell, he held numerous positions including President of the American Psychological Association, Dean of Arts & Sciences at Tufts University, Provost at Oklahoma State University, and professor and center director at Yale. In addition to his contributions to the study of wisdom, Dr. Sternberg is well-known for his work in creativity, love and hate, and the Triarchic Theory of Intelligence.

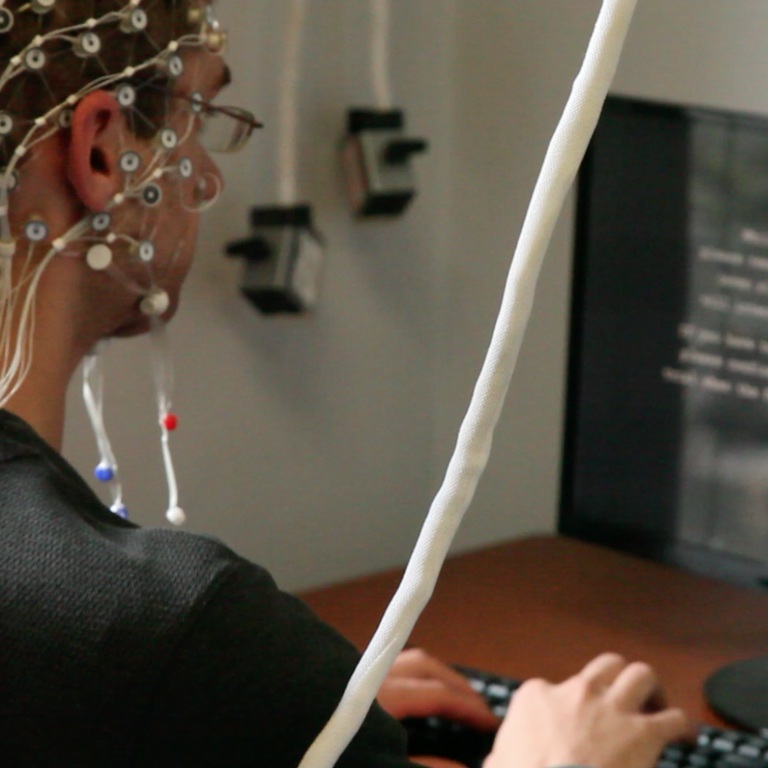

The following is an excerpt from the documentary film The Science of Wisdom. In this interview, Dr. Sternberg discusses his Balance Theory of Wisdom, and how we can teach for wisdom in schools despite its challenges. He also offers some practical wisdom about the importance of recognizing how we can create false beliefs and self-fulfilling prophesies for others and for ourselves, and if left unchecked, how these false notions get in the way of our journey towards wisdom.

Jean: Can you tell me about your research interests?

Dr. Sternberg: Well, I became interested in psychology when I was in elementary school. In my case, as a result of not doing well on IQ tests and wanting to figure out why I did so poorly on IQ tests. So for much of my career I focused largely on intelligence. Then I began to feel like intelligence wasn't the whole story, and that there are people who are smart but not very creative. So I started studying creativity, because I felt that people who were lacking in creativity often got promoted into positions of power and influence on the basis of SATs, and ACTs, and GREs, and GMATs. But they often weren't the right people for the jobs. And then I started studying common sense because I concluded there are people who were analytically smart and creative, but didn't have much common sense. And then I started studying wisdom, because I felt that wisdom went beyond common sense and creativity and intelligence.

Jean: What would you say are your biggest contributions to the study of wisdom?

Dr. Sternberg: My biggest contribution in studying wisdom?.… I think that my two adult children are pretty wise. My second biggest contribution is probably not a very big contribution. I would say it's a small to medium small contribution. It is the balance theory of wisdom.

Jean: Can you explain the balance theory of wisdom and its origin?

Dr. Sternberg: I got interested in wisdom because I saw people who were smart doing foolish things. I even authored a book on why smart people can be so stupid. The conclusion I reached is that people can be really smart in an analytic sense--an SAT sense, but their intelligence actually can interfere with their being wise, because they figure they're so smart they can't do dumb or foolish things. I have seen very smart people in positions of power who become overly optimistic (“if it's my judgment, it must be right”), or egocentric (“it's all about me”), or falsely omniscient (“I think I know everything, because I'm so smart”) or falsely omnipotent (“I’m like Superman”). In some cases, they become ethically disengaged, feeling that ethics are really important for other people but that they've risen above all that. So I came to realize that here were all these smart people doing foolish things. So the balance theory basically was about that. It's applying your abilities, and your knowledge, and your passions for a common good; by looking out for your own interests, but also other people's interest and higher order interests, which could be your state, your community, your country, the world, God--something higher than yourself; by taking into account both short-term and the long-term potential consequences. It's not just doing what is good for others today or tomorrow, but what's good in the long term through the infusion of positive ethical values. To be wise, what you do has to be ethical. And all that is done to adapt to environments (to make yourself a better fit to your environment), to shape environments (to make the environments a better fit to you), or to select new environments--to find new environments that are a better fit for you. I was in a job at one point that was a terrible fit for me: I tried adapting; I tried shaping. Nothing worked. I selected a new environment. In other words, I got out.

Jean: In a paper you wrote in 2004 (What is wisdom and how can we develop it) you outlined 16 principles for teaching wisdom. How readily do you think these principles in general could be incorporated into an actual school setting?

Dr. Sternberg: I don't think the difficulty is in incorporating them into a school in the abstract. It's that there are contextual difficulties. There are a few problems. One is standardized testing, which doesn't assess wisdom. There isn't much incentive for teachers to stress wisdom if that's not the way they're going to be evaluated, not how the kids are going to be evaluated, not how the school is going to be evaluated. A second problem is the teachers never were trained to teach for wisdom. So it's not easy for them because that's not what they learned how to do. The third problem is that it's not something necessarily that school systems and parents are going to support. They may feel like it is hard enough for kids to learn the facts. What's the point of all this wisdom stuff? For some people it would sound ideologically motivated even though it isn't--like some kind of perverse leftist plot. And I think a fourth problem is ensuring that teaching for wisdom fully integrated into the curriculum rather than, “well, now we're going to do our wisdom exercise,” or “today is wisdom day.” Teaching for wisdom really has to be part and parcel of the whole thing rather than sort of separated into wisdom exercises as separate entities. I think it could be done, but there are challenges.

Jean: Since 2004, have you heard of any schools that have tried to incorporate any aspects of these principles?

Dr. Sternberg: Yes, I have. In 2005, I went into administration and I had an agenda that included teaching for wisdom in college. The idea was to incorporate wisdom both into the curriculum and into admissions. When I was Dean of Arts and Sciences at Tufts, we created a project called Kaleidoscope, which supplemented tests like the SAT and the ACT with measures that assessed creative, analytical, and practical ways of thinking. When I became provost at Oklahoma State, we had a project called Panorama, which did something similar. It was based on research I had done when I was a professor at Yale. So I know it could be done if there is top-down and bottom-up support for doing it.

Jean: So I'm going to come back to your most important contribution to wisdom…being your children. Were there specific things that you taught to them to help to develop wisdom as they grew?

Dr. Sternberg: I was just listening to an interview on the BBC while I was driving to work today. And during the interview (on front trading), I thought a problem with much of our society is ethics -ethical disengagement from other people. What I tried to teach my young kids is that ethics are not only for other people; they are for you. Ethics are not just for ethics class or religious services or Sunday school. They are something you should incorporate into your everyday life all the time. So what I have encouraged my kids to do is not to go for the prestige or the money; go for the fit. Find the place that is the right place for you and you're the right person for them, and that's where you'll have the best life. And that applies, as well, to my own life. I've had several jobs at universities. I've worked at Yale, and Tufts, Oklahoma State, the University of Wyoming, and now Cornell, and all but one were a pretty good fit. And what I came to realize is the importance of adaptation, shaping, and selection. When it's the wrong environment and you can't shape it, get out. And that's true whether it's a job or an interpersonal relationship. I think you role model wisdom and ethics for your children, and you teach them that these are important principles-- looking out for others, not just for yourself; looking out for the long term, not just what makes you happy today; and balancing your own and others' interests with larger interests. That's a very important thing to do every day.

Jean: In our interviews and in the research that we've done in the lab, wisdom correlates with experience. Is there a specific experience, if you were speaking to a group of youth, that you would share with them?

Dr. Sternberg: Oh, well, first of all I think that what's important is not experience but rather what you learn from it. There are people who have a lot of experience, but who don't learn much from it; and they keep making the same dumb mistakes. I think that the experience that has possibly had the most influence in my life was that when I was in elementary school and I did poorly on IQ tests, as I mentioned before. I like to think it was because of test anxiety although I realize there are alternative explanations. As a result of doing poorly on the tests, my teachers thought I was stupid. I thought I was stupid. I did stupid work. The teachers were happy I did stupid work because people are happy when you give them what they expect. I was happy that they were happy and everyone was pretty happy. So it was a nice happy group. And then in fourth grade I had a teacher who thought there's more to a person than an IQ test score. She had higher expectations for me, and I went from being a mediocre student to being an A student. So I think for me, that experience affected my whole life and my research career. We often inadvertently set up self-fulfilling prophesies for others but also for ourselves, and we don't realize the extent to which we make them come true. I've seen it in my own life. I've always thought I'm pretty bad at spatial kinds of things. I don't visualize well, and so I had trouble following directions. But once, when I was in a dangerous part of a city at night, I had to get out of it or really put myself at risk. I got out fine. And I realized that because I'd always thought I was bad at spatial relations I never really listened to directions. I always got lost and it always became a confirmation of a belief upon myself, which wasn't that accurate. So that was kind of it-- if you expect a lot from people and you help them develop their strengths, you get a whole lot more than if you (consciously or unconsciously) write them off as losers; then they often become losers. And that not only means other people…that means you yourself.

Robert Sternberg, Ph.D.

Professor of Human Development at Cornell University

Reference

The Science of Wisdom, produced by the JJ Effect, directed by Jason Boulware