by Robert Roy Britt, Elemental

Asked by researchers to reflect on the disagreements they have with others, an astonishing 82% of people said they were usually right and the other person was usually wrong. That’s impossible math, of course, and it is just one example of our collective lack of wisdom, and how hard it can be to gain some.

If wisdom came with age or smarts, we would all be a lot more tolerant, considerate, and respectful of others, according to a vast body of research on the topic. We’d listen more, spout less, and be more thoughtful about contradictory information and opposing opinions. Our world would be less polarized and acrimonious.

We’d feel better, too.

“Emerging research suggests that wisdom is linked to better overall health, well-being, happiness, life satisfaction, and resilience,” scientists concludedin a review of research published in the Harvard Review of Psychiatry. While there’s no proof that being wiser will make you healthier, the insights that come with wisdom are said to bring greater individual well-being though increased acceptance, gratitude, and calmness, all of which means less anxiety and depression.

But alas, neither age nor intelligence automatically beget wisdom. Instead of growing wiser, most of us just become more intellectually inflexible with time, our beliefs more resolute, our minds increasingly closed off to opposing facts and views.

Meanwhile, if our increasing inability to agree on anything these days serves as a gauge, wisdom is on the wane.

What is wisdom?

One reason we’re all not wiser is our utter lack of understanding about what wisdom actually is and how to use it, well, wisely.

For thousands of years, wise people across multiple cultures — from Buddha to Plato to Gandhi — have tried to define wisdom. Yet a universal definition remains elusive, even among modern big thinkers who study its many aspects, sources, and benefits. Dictionaries fall well short, with simplistic but popular definitions like “good sense or judgment” or “the natural ability to understand things that most other people cannot understand.” Socrates gave us a succinct but not-so-helpful take: “The only true wisdom is knowing you know nothing.”

In theory and in practice, however, wisdom is all these things and so much more.

“Wisdom is more about acquiring a deeper understanding about meaning in life, of being able to see how and where you fit into the grander scheme of things and how you can be a better person for yourself and for others,” write co-authors Dilip Jeste, MD, a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at the UC San Diego, and Scott Lafee, in their 2020 book Wiser.

What wisdom is not

While it’s hard to pin down exactly what wisdom is, studies have shown clearly what it is not.

Wisdom is not age nor experience. The phrase “older is wiser” can be false as often as true. “Wisdom and age are not inextricably bound,” Jeste and Lafee write. Wisdom often comes with age but, to paraphrase Oscar Wilde, sometimes age comes alone. Put another way: Young people are often the wise ones, even if us older folks won’t listen to them. “Some people garner wisdom sooner than others,” said the late Dolores Pushkar, who taught and researched psychology at Concordia University in Canada. “That’s why we call them old souls, since they are quicker to learn what leads to a better life.”

Wisdom is not intelligence. Wisdom requires some intelligence, but smart people aren’t necessarily wise. Pick your most-loathed politician or billionaire. Wise people are also compassionate and open-minded. “They listen and make others feel heard,” Jeste and Lafee explain. “They are reflective, unselfish, and problem-focused. They are willing to act on their beliefs and convictions, to do what is right, first or alone.”

Wisdom is not emotional detachment. Wise decisions and actions are linked not just to IQ but to EQ, or what scientists call “emotional intelligence,” according to a pair of studies published recently in the Journal of Positive Psychology. “Sometimes emotional cues can be really important information for understanding other people, and to wisely maintain your social relationships and ultimately have human flourishing,” says study team member Yena Kim, a behavioral-science PhD student at the University of Chicago.

The elements of wisdom

Perhaps wisdom is best understood not by a definition, but by its characteristics. In a study published last month in the International Psychogeriatrics journal, Jeste and colleagues propose seven traits that determine a person’s level of wisdom:

- Self-reflection: Understand your own thoughts, motivations, and actions.

- Prosocial behaviors: Maintain positive social connections and act with compassion, empathy, altruism, and a sense of fairness.

- Emotional regulation: Manage negative emotions and stress that can get in the way of decision-making, and lean into positive emotions.

- Acceptance of diverse perspectives: Learn about and accept perspectives and value systems outside your own.

- Decisiveness: Make decisions in a timely manner with comfort.

- Social advising: Give good advice to others.

- Spirituality: Connect with yourself, with nature, or with a transcendent entity such as the soul or God.

The importance of these qualities was made evident previously, in a 2018 study in which Jeste’s team interviewed hospice patients who were in their final months of life. Asked about the components of wisdom, given their new perspectives on the meaning life as its end neared, the patients cited these characteristics, in this order of preference:

- Prosocial behaviors

- Social decision making

- Emotional regulation

- Openness to new experience

- Acknowledgment of uncertainty

- Spirituality

- Self-reflection

- Sense of humor

- Tolerance

“They emphasized how much they appreciated life, taking time to reflect,” said the study’s lead author, Lori Montross-Thomas, PhD, a UC San Diego assistant professor of medicine and public health. “There was a keen sense of fully enjoying the time they had left and in doing so, finding the beauty in everyday life.”

A wise move: Get over yourself

Perhaps the biggest hurdle to wisdom is a lack of intellectual humility — the awareness that — horrors! — we might be wrong now and then, that some of our views and opinions could be based on incomplete or flawed information.

No matter how much you and I might disagree, research suggests we’re both right, at least in our minds.

A few years ago, Mark Leary, PhD, an emeritus professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University, conducted that compelling survey in which people were asked to characterize their disagreements, resulting in the mathematically impossible 82% saying they were usually right and the other person was usually wrong.

“When it comes to our beliefs and opinions, most of us are much more confident than we should be,” Leary says.

There’s an interpersonal cost to lacking intellectual humility: It makes a person less likely to compromise and more likely to cause friction in relationships.

Guys, take note:

“Women whose partners scored lower in intellectual humility indicated that, during disagreements, their partners tried less hard to understand their position and were more likely to storm out of the room,” Leary writesin Psychology Today. “Men low in intellectual humility also rated their partner as less intelligent, presumably interpreting her failure to agree with him as a sign of stupidity. The data suggest that men who are low in intellectual humility are particularly disrespectful and dismissive when their partners disagree with them.”

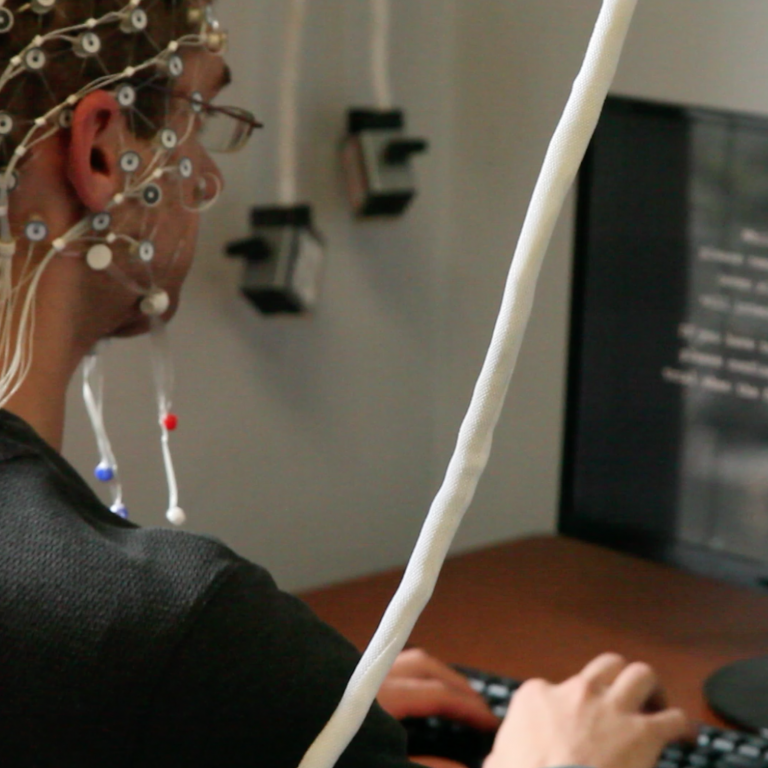

Part of the problem is that hardheadedness—our tendency to consider only confirming evidence—is at least somewhat hardwired. Without us even realizing it, the brain tends to block out legitimate facts that contradict our views, a study involving brain scans revealed last year.

“Our brains become blind to contrary evidence when we are highly confident, which might explain why we don’t change our minds in light of new information,” said study leader Max Rollwage, a doctoral student at University College London’s Wellcome Center for Human Neuroimaging.

If you think this isn’t you, consider that this confirmation bias, as scientists call it, is among the top reasons why bogus conspiracy theories flourish — and we’re all vulnerable, surveys and studies show.

So what’s the secret to getting over ourselves?

In one study, Leary’s team found that intellectually humble people pay more attention to the quality of evidence on which they base their views. They also:

- Question their own opinions

- Reconsider based on new evidence

- Recognize the value in others’ opinions

- Like finding new information that challenges their beliefs

Day-to-day wisdom

For wisdom to be useful, we need to draw from it when the chips are down, like when we’re in an argument or struggling with a tough challenge. But like wit, stupidity, or any other human trait, wisdom is not a characteristic most of us can embody 24/7. We can be sage in one moment or one situation, foolish in another, says Igor Grossmann, PhD, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Waterloo in Canada.

“We cannot always be at the top of our game in terms of wisdom-related tendencies,” Grossmann says. “Situations in daily life affect our personality and ability to reason wisely.”

In a series of experiments with 693 people trying to solve personal conflicts, Grossman and a colleague found that individuals tend to show greater wisdom — based on intellectual humility, recognizing the perspectives of others, and searching for compromise — when pondering the problems of others compared to their own challenges. These findings held up regardless of each person’s overall level of wisdom.

Further, we tend to reach the wisest conclusions when contemplating problems faced by loved ones or colleagues at work, not when trying to solve our own problems. “In those situations where we might care the most about behaving wisely, we’re least likely to do so,” Grossman writes.

And get this: People 60 and older exhibited no more situational wisdom than those ages 20 to 40.

“Contrary to the adage ‘with age comes wisdom,’ our findings suggest that there are no age differences in wise reasoning about personal conflicts,” the researchers concluded in the journal Psychological Science.

Ways to become wiser

Wisdom can be learned, but a word to the wise and the unwise alike:

“One can certainly teach people the virtue of such principles as intellectual humility,” Grossmann says. “But one may not be able to recognize the situations when this knowledge may be needed most.”

Among the challenges for Americans and other Westerners seeking wisdom is the simple fact that intellectual humility is not prized nor taught here to the degree seen in Japan and other Asian countries. As one example, elementary school textbooks in Japan emphasize the value of taking another person’s perspective, whereas U.S. textbooks focus more on individual achievement, Grossmann points out. Here’s what that leads to, he and colleagues concluded in a 2012 paper:

“Younger and middle-aged Japanese showed greater use of wise-reasoning strategies than younger and middle-aged Americans.”

One way to make wiser decisions, Grossmann suggests, is to try and distance yourself from yourself. Ask yourself: “How would I respond a year from now?” Or try using the third person to ask: “What does she or he think?” instead of “What do I think?” Conducting such an exercise in writing — as in a diary — can be even more effective, one of his studies found.

Whether you agree or disagree with any of this, bridging the widening ideological chasm in our society and the river of rancor that runs through it would require, say, 82% of us get over ourselves just a little bit and employ some of the wisdom that can come with age… if only we’re wise enough to seek it and patient enough to work at it.

“No one goes to sleep a fool and wakes up wise,” Jeste and Lafee write. “Becoming wiser is a process.”

Click on the citation to read the original post: